Primary hypertension is responsible for 95% of cases of hypertension. It is defined as a sustained blood pressure above 140/90 with no clearly identifiable cause (it is also known as ‘essential’ hypertension).

Introduction

Introduce yourself to the patient with your name and role, and confirm the patients name and date of birth. Wash your hands. Explain the procedure, check the patient’s understanding and obtain consent.

Ensure that the patient is comfortable, check that they are not in any pain and ask which arm they would prefer to use for the procedure. Request the patient to adequately expose their arm by rolling up their sleeves or removing garments if necessary.

Warn the patient that, although the procedure should not be painful, it is normal for the cuff to feel uncomfortable or tight and that some people experience pins and needles in their hand. Let them know they can ask you to stop at any point.

Equipment

You will need to collect:

- Sphygmomanometer (manual blood pressure cuff).

- Stethoscope.

History

It is best practice to allow a patient a few minutes to sit still and relax before taking a reading to ensure accuracy, so it makes sense to fill this time with some relevant questions. In order to put any readings you obtain in to context you will need to know some basic information about your patient.

Past medical history

Ask the patient if they have known hypertension, and if they do, ask if they have a record of their readings at home for comparison. Identify which arm they usually take their readings from to ensure consistency.

Enquire about any other known medical conditions. There are multiple secondary causes of hypertension.

Secondary hypertension is responsible for 5% of cases of hypertension. It differs from primary hypertension in that it has an identifiable underlying cause. There are many causes of secondary hypertension.

Endocrine:

- Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's syndrome).

- Cushing's syndrome.

- Acromegaly.

- Hyperparathyroidism.

- Phaeochromocytoma.

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (11-beta hydroxylase deficiency).

- Liddle's syndrome.

Cardiac:

- Aortic coarctation (arm hypertension).

- Aortic stenosis.

- Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

Renal:

- Glomerulonephritis.

- Renal failure.

- Renal artery stenosis.

- Pyelonephritis.

- Adult polycystic kidney disease.

Other:

- Pregnancy.

- The combined oral contraceptive pill.

- Scleroderma.

- Steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Social history

Include questions about alcohol, smoking and dietary fat and salt intake in your history. This provides helpful background information on potential risk factors. Recent stresses or a lack of sleep can also affect a person’s blood pressure. Pregnancy is another thing to bear in mind; blood pressure reduces in the second trimester, so a greater than normal result is abnormal, and could suggest gestational hypertension, or even pre-eclampsia.

The risk factors for essential hypertension can be divided into modifiable and non-modifiable.

Modifiable:

- Alcohol.

- High fat or high salt diet.

- Obesity.

- Smoking.

- Stress.

- Lack of sleep.

Non-modifiable:

- Ethnicity.

- Family history.

- Sex and age: The risk to those less than 55 years of age is greater in males than in females, whereas after 55 years, females are at a greater risk than males. .

Recent history

Ask the patient about their day leading up to their appointment to check for things that may have recently affected their blood pressure. Caffeine consumption and exercise can temporarily raise blood pressure, and should ideally be avoided before readings are taken.

Procedure

Ensure the patient’s preferred arm is placed comfortably at around heart level. Check that you are using the correct size cuff and that is it deflated (by opening the valve).

Palpation

Palpate for the brachial pulse, medial to the biceps tendon. Line up the arrow marked on the cuff with the brachial artery and fasten the cuff around the patient’s arm.

Ensure that the valve is closed on the hand pump. Inflate the cuff whist palpating the radial pulse. At the point where you can no longer feel the pulse, read the meter; this is a rough estimate of the patient’s systolic blood pressure.

Auscultation

Deflate the cuff and close the valve again. Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope over the brachial pulse, just under the cuff.

Place the diaphragm just under the cuff.

Inflate the cuff to 20mmHg above your estimated systolic pressure. Next, by minimally opening the valve, slowly deflate at around 2-3mmHg/s, whilst watching the pressure dial.

Listen carefully for loud beating sounds called ‘Korotkoff sounds.’ When you first hear the sounds, read the meter; this will be the systolic pressure. You will continue to hear the sounds for a brief amount of time. Once the sounds have completely died away, read the meter again; this will be the diastolic pressure. Readings are usually taken to the nearest 2mmHg.

Systolic pressure is the maximal pressure in the aorta generated by the heart in ventricular systole. This is normally <120mmHg. Following systole, the pressure in the aorta will reduce, although it will be maintained at a high level by the elastic recoil of the aorta. The lowest aortic pressure, termed the diastolic pressure, will be present just before the next occurrence of ventricular systole.

Confirmation

If the reading is abnormal or different than expected, repeat the procedure to be sure of your result. Take the lowest reading and record this in the notes.

Explanation

In practise, you will then need to explain the result to the patient. It is likely you will also need to do this in an OSCE scenario.

If you haven’t already, look for past readings to compare against and check for reasons why the patients blood pressure might be high.

Blood pressure classification

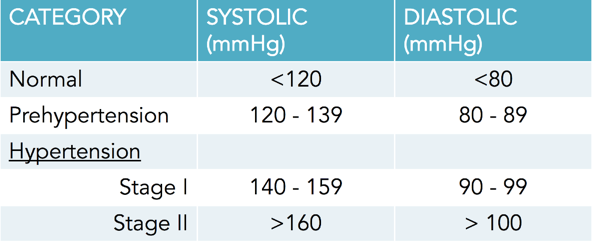

Hypertension is defined as a blood pressure >140/90 – the level above which treatment has been shown to decrease progression and risk of disease.

The risk of cardiovascular events doubles for every 20/10mmHg rise in blood pressure.

Table defining the boundaries of prehypertension and hypertension.

Severe hypertension

Once blood pressure reaches levels over 180/120, there is a real risk of organ damage, resulting in what is known as severe hypertension. Delicate organs such as the eyes and kidneys are particularly vulnerable to the high pressure. If these are damaged this is known as malignant hypertension.

Damage in the eyes causes visual disturbances, whereas kidney damage presents with urinary signs such as haematuria. The brain can also be affected, leading to encephalitis, causing confusion and fits. Eventually congestive cardiac failure will develop due to the excessive strain of pumping against such high systematic pressure.

One non-invasive diagnostic test is fundoscopy. There are four signs of hypertension that are identifiable on fundoscopy, corresponding to the four stages of hypertensive retinopathy. These are:

- 1. Silver wiring.

- 2. Arteriovenous nicking.

- 3. Flame haemorrhages.

- 4. Papilloedema - diagnostic of malignant hypertension.

Prognosis

If uncontrolled, hypertension can lead to an increased risk of:

- Stroke (both ischaemic and haemorrhagic).

- Myocardial infarction.

- Heart failure.

- Chronic kidney disease.

- Peripheral vascular disease.

- Cognitive decline.

- Premature death.

Management

Hypertension can be managed both conservatively and medically.

Conservative management

There are a number of steps that can be taken before pharmaceutical intervention is required:

- Reduce salt intake.

- Lose weight.

- Take regular exercise.

- Stop smoking.

- Reduce alcohol intake.

- Improve sleep hygeine.

- Reduce stress levels.

Medical management

In addition to the above it is also worth investigating to identify prognosis and possible causes. These can include an ECG/echocardiography, fundoscopy, a urine dip test and routine blood tests.

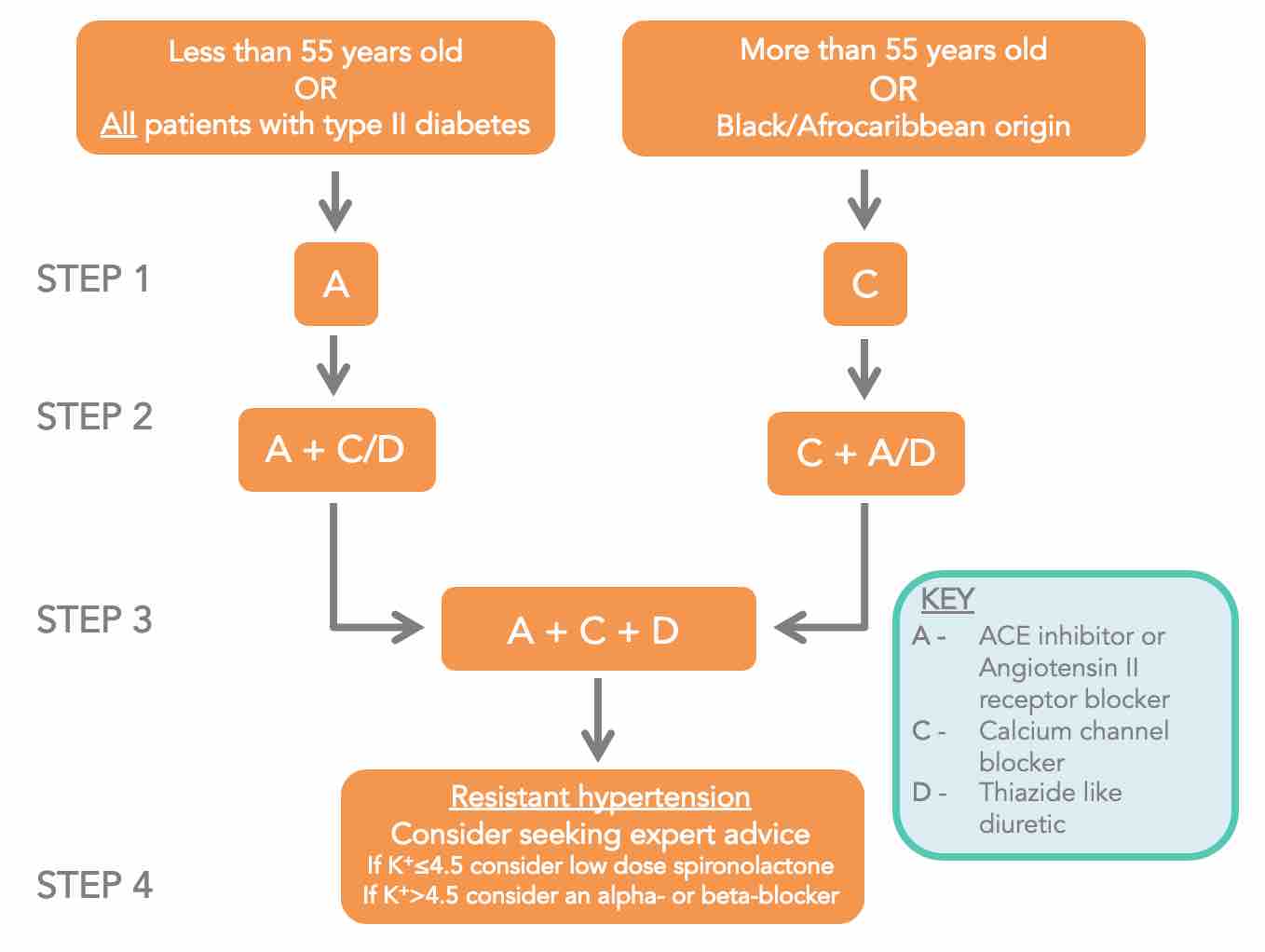

If a cause of secondary hypertension is identified, then this will be treated appropriately. Otherwise, it is assumed that the patient has primary hypertension, and this can be managed with the treatment algorithm recommended by the British Hypertension Society and NICE:

Treatment algorithm recommended by the NICE.

The goal of management is to keep blood pressure <140/90.

- If the patient is greater than 60 years of age, aim for <150/90.

- However, in diabetics and those with chronic kidney disease, still aim for <140/90.

- ACE inhibitors prevent the formation of angiotensin II. This allows vasodilation, which lowers total peripheral resistance, resulting in a reduced blood pressure.

- As shown in the algorithm, ACE inhibitors they are first line for treatment of hypertension in patients less than 55 years of age and not of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity, and any patient with type II diabetes mellitus. This is because of ACE inhibitors have renoprotective effects.

- ACE inhibitors are contraindicated in renal artery stenosis (RAS), as action on the glomerular efferent arterioles can lead to a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate. Therefore, two weeks after starting ACE inhibitors, check blood urea and electrolytes to assess for damage suggesting undiagnosed RAS.

- A common side effect of ACE inhibitors is a dry cough, due to an increase in levels of bradykinin. Warn patients about this; if a cough does develop you can switch to an angiotensin receptor blocker instead.

- Calcium channel blockers work by inhibiting the entry of calcium into the smooth muscle of the heart and peripheral arteries. This reduces electrical conduction within the smooth muscle, decreasing the force of cardiac contractions (thus lowering cardiac output) as well as relaxing and dilating arteries (lowering total peripheral resistance).

- As shown in the algorithm they are the first line treatment for hypertension in non-diabetic patients over 55 years of age or of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity.

- Common side effects include ankle-swelling, facial flushes and headaches.

- Thiazide diuretics control hypertension by inhibiting reabsorption of sodium and chloride ions in the distal convoluted tubules in the kidneys. This leads to reduced water retention and a greater urine output, resulting in a reduction in total blood volume.

- Thiazide-like diuretics (such as indapamide) act to produce a similar but greater effect. As shown in the algorithm, these are used as a second or third line treatment for hypertension, in combination with ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers.

- Common side effects include low sodium and potassium levels which can lead to confusion and arrhythmias in extreme cases.

Summary of the above

- 1. Classify the level of hypertension and relay this to the patient.

- 2. Explain meaning, prognosis and potential complications to the patient.

- 3. Investigate to identify any cause(s) or the possibility of any end organ damage.

- 4. Manage the problem based on the cause, first conservatively and then medically or surgically if required.

Completion

Ensure the patient is comfortable and ask if they have any further questions. Thank the patient and wash your hands. Document your findings and note your treatment plan going forward.